History and Landscape in Jamaica Kincaid's "Song of Roland"

Jamaica Kincaid foregrounds a love story in “Song of Roland." But the love story quickly becomes a backdrop for the story’s true preoccupation: the highly charged power asymmetries roiling beneath its surface. Political and gender struggles leave traces in the flesh and behaviors of the characters, so that the struggles become larger, more elemental than the characters, who are often only partially aware of them. Even the island setting—its topographical features and its moody weather—becomes a character of sorts, with agency and motives, almost more real than the unnamed protagonist and her lover. Despite the story’s surface, its undercurrents concern power: power’s uses and power’s limits, and the way power is exercised by the powerless.

Most of the story is told in iterative time. The narrator and her lover meet again and again in an ongoing tryst, lending the romance a sense of the timeless, the mythological. Three exceptions, each including pages of sensual detail, anchor the narrative specifically in time and place: first, when the lovers meet during a rainstorm (indeed, the rainstorm seems partially responsible for their meeting). The narrator’s dress is plastered alluringly against her body; she must take shelter beneath a gallery. Her mood—which we eventually recognize as one of her chief coping strategies—is one of sublime desolation: “I was standing under the gallery,” she says, “enjoying completely the despair I felt at being myself” (147). She is receptive, in such a mood, to the aesthetic pleasures of romance. It seems as though Roland is as well, for she manages to communicate with him over a din of sadness: the people around them, speaking loudly of “…their disappointments… for joy is so short-lived there isn’t time to dwell on its occurrence” (148). The narrator derives her power from her ability to turn sadness and squalor into transcendent beauty so as not to be subsumed by it—she possesses the power of the artist.

The second instance of specific time occurs when the narrator has a confrontation with Roland’s wife. While the older woman hurls exaggerated invective at her—“…[she] called me a whore, a slut, a pig, a snake, a viper, a rat, a low-life, a parasite, and an evil woman” (151)—she keeps herself emotionally distant from the insults and blows, safe within another source of her power: her youth, beauty and indifference. “I was then a young woman in my early twenties,” she confides, “my skin was supple, smooth, the pores invisible to the naked eye” (151). While Roland’s wife, enraged, rips the narrator’s dress from her body, listing the names of his other lovers, the narrator coolly observes that “The impulse to possess is alive in every heart, and some people choose vast plains, some people choose high mountains, some people choose wide seas, and some people choose husbands;” adding, significantly, “I chose to possess myself” (152-3). The narrator is assured victory over her body and mind—unlike the other battlegrounds over which the characters fight and exhaust themselves.

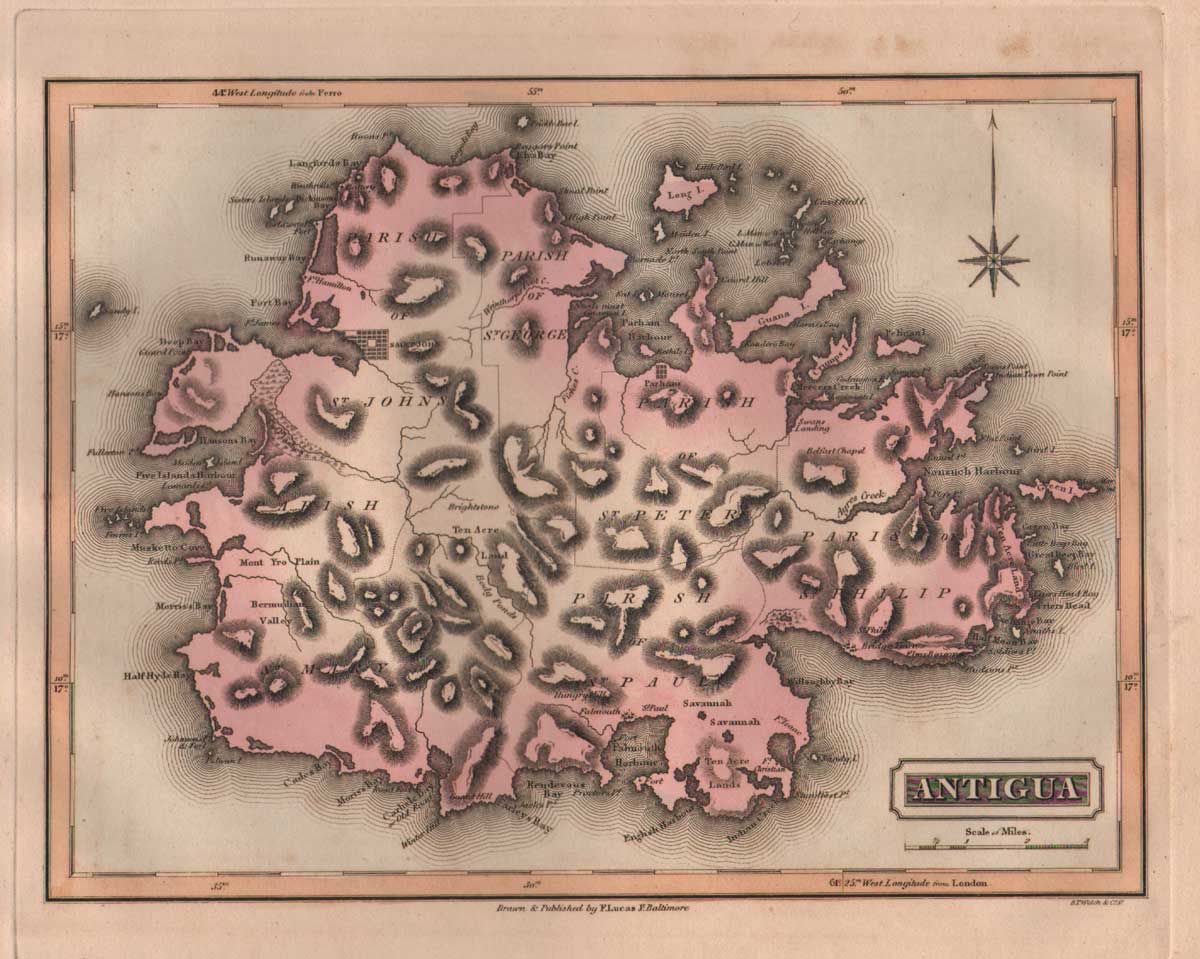

The story’s ultimate scene sets the narrator and Roland facing the sea that can’t free them, with their backs to the island that traps them, the “…small world we were from, the world of… steep mountains… covered in a green so humble no one had ever longed for them, of three hundred and sixty-five small streams that would never meet up to form a majestic roar… of people who had never been regarded as people at all” (155). The narrator looks in the direction of the horizon. She can’t see it but knows it’s there, and she likens this unseen limit to the limit on her love for Roland. It will end, she’s foreseen, like the island’s three hundred and sixty-five streams: “[it would]… spill out of me and run all the way down a long, long road and then the road would come to an end and I would feel empty and sad…” (149). The island’s geography serves as an extended metaphor for the emotional limits it imposes on its inhabitants.

These three specific scenes, set within skeins of recursive time, do little to make the romance more concrete. Instead, what they highlight is the story’s preoccupation with themes of power and powerlessness. From their first meeting, the narrator asserts that Roland, “…was not a hero,” and unlike the emblem of chivalry to which the story’s title alludes (Childress), “…he was a small event in someone else’s history” (148). In her tenderest explorations of love, the narrator employs the language of war and conquest: “When our eyes met,” she says, “we laughed, because we were happy, but it was frightening, for that gaze asked everything: who would betray whom, who would be captive, who would be captor…” (148); Roland’s mouth, she asserts, was “…like a chain around me” (148); when he kisses her breasts, she can’t decide “…which sensation I wanted to take dominance over the other” (152); and when Roland’s wife confronts her, she tells the younger woman, “…[Roland’s] history; it was not a long one, it was not a sad one, no one had died in it, no land had been laid waste, no birthright had been stolen; she had a list, and it was full of names, but they were not the names of countries” (152). In this story, a romance is a conquering, with a victor and a loser. The lovers have been robbed of country, history, birthright and even personhood (a people “…who had never been regarded as people at all,”) and their attempts to reclaim are enacted on one another’s bodies. In this way the subtle shadow of colonial slave heritage stretches over the story, as inevitable as the weather (which, as the narrator asserts, is, “by now beyond comment” [148]). If the story’s landscape circumscribes, its history binds with an even tighter chain.

The narrator triumphs because she refuses Roland’s “silent offering” (154). She remains in control of her fertility, which Roland wants—without understanding his want—to plunder, like he plunders the wombs of the ships whose lading he steals. She is so confident in her victory, she can empathize with her would-be possessor: for “…no mountains were named for him,” she says, “no valleys, no nothing… no history yet written had embraced him” (154). She can see that his need to conquer women is a proxy to remedy the shame of these losses, and that he can’t fully understand the “small uprisings” within him that urge him to all this small-scale conquering. Roland, like the narrator, wants a story of his own. But once again, as in times past, he has been hijacked by history. He has only the narrator—the artist—to sing his small and humble song.

Cited Sources

Childress, Diana. “The Song of Roland.” Calliope. March, 1999. Vol. 9 Issue 7. Web.

Kincaid, Jamaica. “Song of Roland.” More Stories We Tell: The Best Contemporary Short Stories by North American Women. Ed. Wendy Martin. New York. Pantheon Books. 2004. 146-55. Print.