Psychological and Sociological Transhumanism in Videogames

Videogames are transhuman experiences. Our bodies and minds temporarily enter into a collaboration with technology for the purpose of bringing about specific results in virtual spaces. Two recent games explore transhumanism explicitly, removing us entirely from a human context in order to force a confrontation with what it means to be human. 2021’s Returnal and 2022’s Stray smuggle very sophisticated literary theory into the grammar and topoi of traditional third-person shooters and puzzle platformers respectively. Though videogames are often overlooked as literature, the act of participating in a narrative gives players a different orientation to the content, due to the combination of poetics and procedural rhetoric, that actually leads to a transhuman sense of game-player co-authorship.

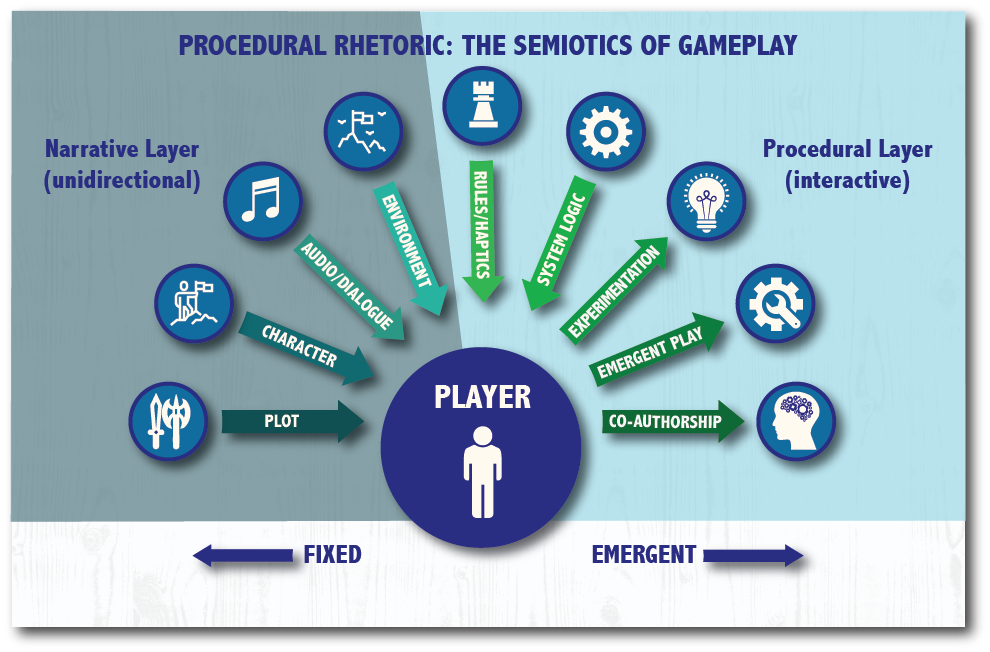

The term “procedural rhetoric” was coined by Ian Bogost to refer to the interactive game processes that encourage certain behaviors over others; a semiotics of gameplay. Like other media, games have a narrative layer that is unidirectional: Plot, character, setting, and dialogue are fed to players and amplified by musical scores, cinematic cut scenes, and environmental dynamics. Players receive this layer passively. But, as Jesper Juul contends, we cannot understand the persuasive power of videogames unless we analyze their narratives in tandem with their rules. “The player navigates… two levels,” he says, “playing video games in the half-real zone between the fiction and the rules. (Juul 202)

Rules are communicated via the mechanical and haptic feedback that occurs beneath the narrative in a process which Bogost defines as “the art of persuasion through rule-based representations and interactions” (ix). The reciprocal relationship between action and consequence leads to an emergent sense of collaboration that is unique to the medium. Unless developers pay close attention to the synergy between the procedural and narrative rhetorics, conflicts can arise between them, causing what game developer Clint Hocking terms “ludonarrative dissonance.” If the narrative of the game insists that pacifism is a moral good, for instance, but the game’s mechanical systems make virtual murder pleasurable or rewarding in goods and XP, the player experiences a disconnect between the two rhetorical overlays.

Sometimes games leverage this dissonance. I’ll give just a brief overview of how Returnal and Stray use procedural rhetoric to generate dissonance. These games use disorientation to jolt players to experience, to “play,” psychoanalytic and Marxist theory respectively. Returnal is a shooter about an “Astroscout” who crash lands on an alien planet. The alien civilization is long gone, but Selene must fight her way through the automated defenses that remain while making an upward journey through different biomes to find a means of escape. These are all very recognizable—one might even say cliché—gaming tropes. The dissonance occurs after about 15 hours of gameplay when events lead players to realize suddenly that the alien landscape through which they have been fighting takes place entirely within the protagonist’s psyche, and this genre switch reorients them to their role in the story. We are not on an alien planet at all, and all events and characters map seamlessly onto ideas drawn from Freudian literary theory, wherein the game tropes of fighting swarms of enemies become a metaphor for battling inner demons; the three main characters become analogs of Freud’s tripartite self; and the respawning after in-game death becomes an example of the repetition compulsion.

Like Returnal, Stray is a journey upward, but it examines the sociological remnants humanity leaves behind. The game takes place in a far future after humanity has wiped itself out. The player embodies a cat that must ascend through the levels of a subterranean city, helping robot denizens who, in the absence of humans, have become self-aware and now simulate human culture, for good and ill. The game becomes a sort of escape from Plato’s cave, with revelations accompanying each level from the bottommost slum of the city to its sleek neon markets above. Interestingly, the robots in the slums are philosophers and artists, having formed strong kinship bonds and community, while the market tier demonstrates the perils of capitalism, representing the robots as mindlessly working to no end: Barbershops and clothing stores open each day even though the robots have no hair or need for clothes; each night they dance identical dances at the nightclub. They betray each other and hoard valueless wealth. The dissonance is produced by players’ identification with hollowness of the human structures, an identification that is not shared by the cat avatar. Players realize, all at once, that they are enmeshed in a critique rather than a game and experience a similar reorientation to the content. It lays bare and savagely critiques the logic of capitalism, which we feel more acutely because it is divorced from its human context.

Returnal and Stray are very recent, and signal a potential watershed in videogame criticism, wherein the transhuman act of playing can help us not just read about but experience theory. Katherine Isbister discusses how players of videogames forge “an identification grounded in observation as well as action and experience.” So games are a form of praxis. By deploying these older critical frames in the service of speculative, posthuman works, we update these tired theories into a contemporary context. These games hint at the near limitless potential of the genre to explore and experience both theory and praxis.