The Then and Now of Politics, Mechanical Reproduction, and the Arts

Art played a key role in the political ruptures that took place between 1927 and 1945, leading to unprecedented global violence and a destabilization of ideological paradigms. During the ramp-up to and aftermath of WWII, three Continental scholars wrote from ground zero, each trying to pin down the shifting definition, character, and function of art, just as it collided with, transformed, and was transformed by technology and politics. In aggregate, the methodology these thinkers posit is now more useful than ever. Siegfried Kracauer’s “The Mass Ornament” (1927), Walter Benjamin’s “The Work of Art in the Age of Its Technological Reproducibility” (1936) and André Bazin’s “The Ontology of the Photographic Image” (1945) move well beyond aesthetics to address an ongoing crisis: At the roiling intersection of politics, technology, and culture, art had become (and remains) a contested site where political propaganda, numbing distraction, and liberatory resistance vie for control. Once art can be mechanically (or digitally) reproduced—once it sheds the ritual function to which it has, for millennia, been bound—to whom does it belong and from where does its value emanate? What does mechanically reproduced art do for us—or against us? These critics found the question urgent enough as political structures were harnessing and weaponizing art. But the question takes on new urgency today, as commercial mechanisms facilitate the acceleration of content-creation, much of it produced by the masses. Crucially, however, at the moment the masses begin to recognize their own conditions under capitalism within this work, the same mechanisms occlude recognition and forestall action. Content-generation becomes a numbing praxis that recursively imitates larger mechanisms of exchange value under capitalist rubrics. Capital thus obfuscates art’s liberatory potential, but if we apply a dialectical synthesis of the theses of Kracauer, Benjamin, and Bazin, we might see a path toward its reclamation.

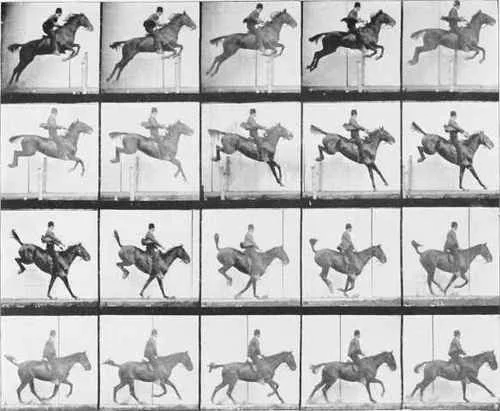

These thinkers were, unsurprisingly, deeply embedded in the drama of their own time and place, but their ideas embody a paradigmatic shift taking place in the early- to mid-20th century that anticipate the media landscape of today. Kracauer begins his essay by outlining an innovative methodology that privileges the analysis of surfaces over depths: “The position that an epoch occupies in the historical process can be determined more strikingly from an analysis of its inconspicuous surface-level expressions than from that epoch’s judgments about itself,” a principle which forms the basis of much of cultural and media studies today (75). He frames his analysis around the geometrical, coordinated movements of the Tiller Girls dance troupe and the orderly rows of anonymous spectators in tiered stands watching them, which he equates with the logic of machinery, assembly lines, and other modes of capitalist production that were gaining traction at the time of writing. In such Taylorized artforms, he argues, “the principle of the capitalist production process… must destroy the natural organisms that it regards either as means or as resistance. Community and personality perish when what is demanded is calculability” (Kracauer 78). Thus, in the words of Paul A. Taylor and Jan LI. Harris, “The fate of the individual body serves as a microcosm of the fate of the body politic,” in which individuality is abstracted into a coordinated whole (49). Kracauer draws a distinction between the anonymity of these new dance styles and older art forms that celebrate individual talent and organic forms, such as ballet. But he notes that capitalism’s core defect is not that it rationalizes too much “but rather too little. The thinking promoted by capitalism resists culminating in that reason which arises from the basis of man” (Kracauer 81). Thus we see mass culture growing toward revelation or understanding but stopping just shy of achieving it. Marx had observed that capitalism trades use value for exchange value and elevates production as end-in-itself, and Kracauer applies Marxist reasoning to art in ways that compellingly prefigure mechanical reproduction’s propulsive acceleration in the digital age: In our time, the cycle of creation and consumption grows increasingly automated—and increasingly detached from any use at all. Algorithms privilege the endless creation of content as an end-in-itself and encourages distracted consumption of this content without the salubrious benefits of contemplation and the changes that might result if we study of art and popular culture critically.

Benjamin’s 1936 essay, on the other hand, regards distraction as potentially constructive, and contemplation as elitist at best: When taken to logical extremes, the fetishization of art’s value, he warns, can serve fascism. “Contemplative immersion—” he said, “which, as the bourgeoisie degenerated, became a breeding ground for asocial behavior—is here opposed by distraction… as a variant of social behavior” (Benjamin 39). It’s no wonder he felt this way: He wrote his seminal essay as the Nazis were amassing power via the harnessing of visual rhetoric, and he knew firsthand the hazards of the “aestheticizing of political life” (Benjamin 41). Unlike Kracauer, Benjamin suggests that the loss of art’s “aura” unlocks its potential to become a mechanism for mass liberation (41). The “aura,” according to Benjamin, is the time- and location-specific essence of a work of art from which it derives cultural value: The work of the “great masters” or the work of ancient civilizations, say, are legitimated and sanctified by association with their contexts. The aura of a Renaissance painting, for example, is a sine qua non of its value, a fact which becomes apparent when a work is exposed as a forgery. Severed from its time, place, and/or artist, the artwork is instantly stripped of any intrinsic value, even if it appears identical. Given the Nazis’ worship of aura—and the anxious way they tried to distinguish art of quality from “degenerate” art—Benjamin saw a latent benefit in mechanically reproduced art created by and for the masses, which is deliberately stripped of aura. The Dadaists, for example, achieved “a ruthless annihilation of the aura in every object they produced” (39). Whereas “A person who concentrates before a work of art is absorbed by it,” he says, “...By contrast, the distracted masses absorb the work of art into themselves” (Benjamin 40). In this configuration, distraction suggests ownership by the masses while concentration suggests ownership of the masses. While Benjamin’s work sometimes feels naïve in today’s context, wherein the restless procession of mass-produced objects seems to merely and dully align with the spirit of capitalism, his warnings at the end of the essay ring true: Society’s “self-alienation,” he argues, “has reached the point where it can experience its own annihilation as a supreme aesthetic pleasure” (42). Indeed, as fascism and the threat of immanent systemic collapse rise in our current moment, we sit immobile, enervated out of the belief that we have any say in our own annihilation. But, again and again, we visit the movie theater, television set, and gaming console to indulge in an aestheticization of apocalypse. Autocorrect suggested “anesthetization.” I’ll keep it. I’ll let “aestheticization” and “anesthetization” hover in prismatic superimposition.

Benjamin’s world, at time of writing, could have gone in either direction: A fascist takeover or a reclamation by the demos, and he died before the end of the war. Not so for Bazin. Unlike Kracauer and Benjamin, Bazin wrote at a moment when fascism, thwarted, was yielding its ideology to a dewy-eyed postwar optimism. This optimism saturates his prose: He clearly sees himself poised at a moment rich with new possibilities. Like his predecessors, he is concerned with a shift in the ontology of art, but the vantage is the dawn of a new era. Bazin argues that for millennia, art’s function was similar to embalming, in that it strove to oppose time. From entombed Egyptian sculptures to the portraiture of royalty, art gave man the “last word in the argument with death” (Bazin 10). Throughout history art was anxiously shored up against annihilation, a striving to preserve life via “a representation of life” (Bazin 10). The advent of photography, Bazin argues, freed the plastic arts to recover their “aesthetic autonomy,” which had been hamstrung by their historical function (16). Today, “the making of images no longer shares an anthropocentric, utilitarian purpose. It is no longer a question of survival after death, but of a larger concept, the creation of an ideal world in the likeness of the real, with its own temporal destiny,” a process that took several hundred years to achieve (Bazin 10). Renaissance painting, he argues, committed the “original sin” of perspective, and thereafter art grew increasingly obsessed with rendering the world with scientific accuracy, and decreasingly concerned with its prior ritual function (namely the spiritual deployment of death-defying symbols). The appetite for illusion, Bazin remarks, little by little “consumed the plastic arts” (11-12). To Bazin, photography is the apotheosis of this trajectory. Photography is thus an agent of liberation that, finally and conclusively, represents the world’s details without man’s anxious need for immortality or mimicry. Freed from their representational shackles, the plastic arts could forge paths yet unknown:

the photograph allows us on the one hand to admire in reproduction something that our eyes alone could not have taught us to love, and on the other, to admire the painting as a thing in itself whose relation to something in nature has ceased to be the justification for its existence. (Bazin 16)

Photography cleans off the “spiritual dust and grime” that human eyes apply to objects—and with which they imbue their paintings and sculptures despite themselves (Bazin 15). Unlike man, the camera is an impartial witness, producing a “hallucination that is also a fact” (Bazin 16). In an era of deep fakes and AI-generated slop, we might balk at the characterization of the camera as “impartial.” Nevertheless, Bazin’s analysis of the trajectory of the plastic arts in their collision with technology remains a useful critical framework with which to explore the arts’ ever-changing function after being liberated from its prior purposes.

While at many points these authors’ media critiques are dated, they each index cultural moments and frame discourse in ways that remain vital. Kracauer offers a methodology—an analysis of surfaces over depths—that is remarkably generative today and has served as the basis for a number of current disciplines; Benjamin proffers an alternative to aura-obsessed fascism on the one hand and the anesthetization of capitalist-controlled technologies on the other, which we should heed today as we are once again poised between these poles; and Bazin lays out a framework by which we can analyze the new functions and possibilities of art once it has been freed from its indentured servitude to psychological and aesthetic obligation. These critics extend Marxist analysis of economic systems into the aesthetic domain, and in so doing expose the deathly grip capitalism has over every global system on earth, including the arts. In Kracauer’s words, “Like the mass ornament, the capitalist production process is an end in itself. The commodities that it spews forth are not actually produced to be possessed; rather, they are made for the sake of a profit that knows no limit” (78). How prophetic of today’s endless churn of content that passes through our feeds and before our eyes, content that contains massive amounts of information but provides no principle of organization through which we might launch a critique. But as later critics such as the new historicists demonstrated, if we look critically at the media around us, we can see within the churn of meaningless content glimpses of the profane and the transcendent. If we change nothing but our critical eye, we might learn to skim over the surfaces of our world, learning about ourselves, our needs, and our fears, and determine whether our systems address them. We might begin to recognize our own conditions under capitalism within the means of communication, see who controls them, and ask ourselves—why don’t we?

Works Cited

Bazin, André. “The Ontology of the Photographic Image.” Translated by Hugh Gray, U. of California P., 2005, 9-16.

Benjamin, Walter. The Work of Art in the Age of Its Technological Reproducibility, and Other Writings on Media. Translated by Edmund Jephcott et. al., Belknap Press, 2008, 19-55.

Kracauer, Siegfried. The Mass Ornament: Weimar Essays. Translated by Thomas Y. Levin, Harvard U. P., 1995.

Taylor, Paul A. and Jan Ll. Harris. Critical Theories of Mass Media: Then and Now. McGraw Hill, 2008.