The Recursive Rhetorical Situation of Charlie Kaufman’s Adaptation

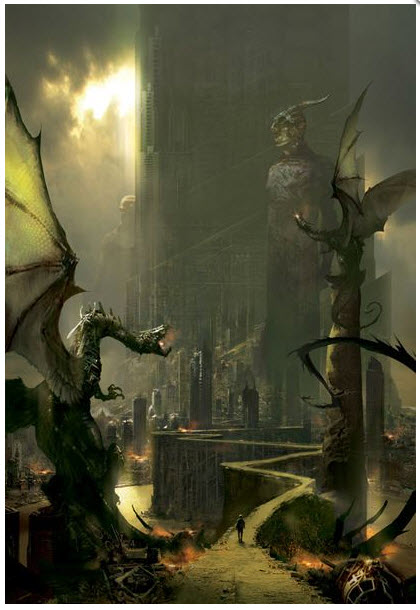

After the runaway success of Being John Malkovich, Charlie Kaufmann turns the focus of his next film not on his ostensive subject, Susan Orlean’s The Orchid Thief, but on himself, dissecting and examining the creative process while trying to adapt an unadaptable book into a film. He paints a portrait of the artist caught in paroxysms of self-doubt, as though he is indeed an insect under the entomologist’s knife. Sweaty, pacing, cowardly with women and in the face of any intimations of joy, the Charlie Kaufman of the film casts his doleful eyes around in paranoid terror while a running inner dialogue hounds his ambient environment. Such a pathetic specimen won’t be well-liked by the audience, so Charlie gives himself a gentler, more centered but commercially-oriented twin brother Donald as a foil. As Charlie, literate and patronizing at first, falls under the influenced by his naïve, puppyish brother, the film’s plot changes direction, veering from an artistic, abstract, pretentious exploration of humans and flowers to an action-driven romantic thriller.

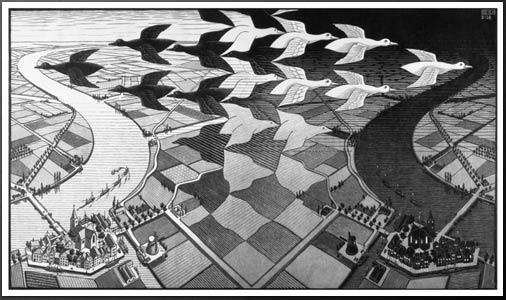

After Donald enters the scene, the movie proliferates with foils. Like the time-lapse photography of plants rearing from the ground, foils begin to grow everywhere, even out of the corpses of previously real-to-life characters. Indeed, the further we get into the plot, the more each character, whether real or imagined, appears to be Kaufman in another guise. They begin as themselves because Kaufman is struggling to see his characters as discrete beings with subjective inner lives, but by the end they are helplessly inducted into his psyche. Even his real-life subject Orlean (played luminously by Meryl Streep) and her subject, the eccentric horticulturalist John Larouche, both end up as phantoms of Kaufman himself, with the former an embodiment of the artist’s sad, luxuriant yearning for Truth and Beauty, and the latter as the incarnation of Kaufman who is pushy and crass, preferring action to self-pity, who has passion and drive and is unflinchingly himself, accepting good and bad alike.

Solipsistic? Definitely. Ego-maniacal? Perhaps. But the film’s solipsism has a point. I am reminded of the quotation, attributed (perhaps apocryphally) to Winston Churchill that “It doesn’t take all kinds, there just are all kinds.” While each character ranges from pathetic to loathsome to unrealistically pure and good, none is complete unto herself. But taken in aggregate, the viewer cannot help but think that it does indeed take all kinds to get a film out of an author and into the world. If the film chronicles the creative process in all its agony and ecstasy, then it pushes acceptance, flexibility, and fusion—adaptation—as the engine that drives creativity. The central drama of the film is not whether Orlean will find the elusive ghost orchid; nor whether she will become a drug addict or ruin her life through her affair with Larouche; nor whether Charlie will overcome his fear of both failure and happiness and “get the girl”; nor whether Donald will wise up to his brother’s resentment. Rather, all aspects of a single person are needed to finish the script, which is the film’s central problem that must be solved (and the viewer is watching the finished product—she knows it happens—but that knowledge does little to undercut the tension). It isn’t the tropes of film genre that drive the action—not the guns, car crashes, deaths, chase sequences, though the film has all those. They feel artificial by design, a scaffold to support the true drama. Time is the enemy that dogs the author—he’s past his deadline, he’s written nothing—and time that creates the plot’s propulsive energy.

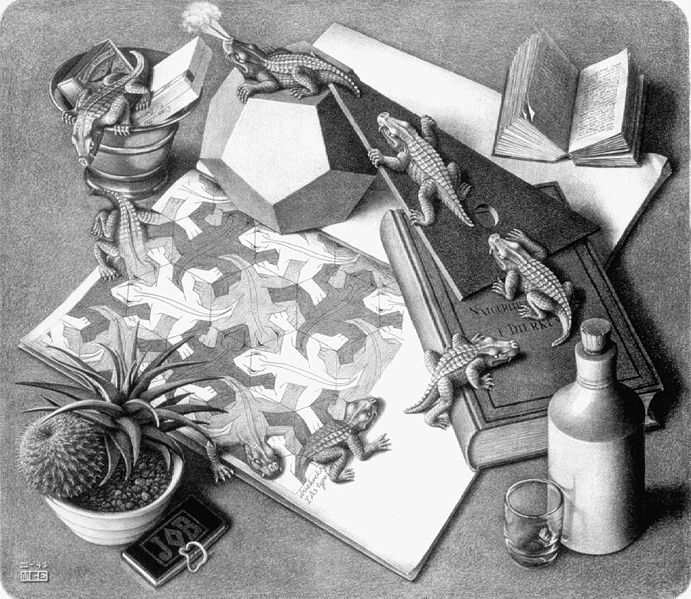

So Kaufman needs to adapt to succeed. He needs to adapt the book into a film, sure, but the adaptation he truly needs is personal and mimics the evolution of flowers to make their own niche within the specific limitations of their environments. Kaufman needs to understand and work within his rhetorical situation, though he doesn’t actually find it until the end. He needs to broker an accord between the aspects of his personality. What we are watching is a film about the artistic process, and the way artists write (or paint or play or nurture) their way into their own rhetorical situations, and the film honors and lampoons this process in equal measure. The story finds its own center through recursive experimentation and iteration, many abandoned and left behind. It’s no wonder the film posters show Kaufman as a plant falling out of a broken flower pot. A final reclamation of sorts happens at the very end, and indicates to the viewer that success has been achieved; voiceovers, so prevalent at the start of the film, stop abruptly when the crusty screenwriting guru Robert McKee says in a lecture “Never use voiceover,” but the final image of the film is of a smiling Kaufman in his car, talking to himself in voiceover and accepting it as his own artistic choice. He has adapted, and the serpent of the film has circled around to grasp its own tail. The book has been adapted, sort of. We can now let time go, landing on a final image of time-lapse flowers growing and dying in front of a backdrop of city traffic.

Evolution achieved.